There’s an adage about making a presentation. It goes: “Tell them what you’re going to tell them. Tell them. Then tell them again.” The point, of course, is to make certain your audience, no matter its size, understands and absorbs your message. The same approach holds true in the context of an employee learning program.

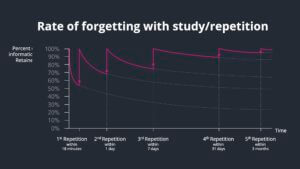

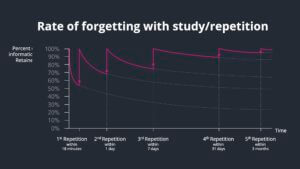

We can thank Hermann Ebbinghaus for that. He’s the German psychologist who advanced the study of memory and is, perhaps, best known for his discovery of the “Forgetting Curve” as well as the related spacing effect, a phenomenon where learning is enhanced when spread out over time. While his work was done in the last years of the 19th century, it’s extremely relevant in today’s world, one marked by many concerned with information overload.

Briefly, Ebbinghaus tested his memory of learnings over spans of time. He then plotted data from his spaced studies and determined the level of memory loss over time. The curve drawn by his data showed that when one learns something, it evaporates from the memory at an exponential rate. In other words, most of what we learn is lost in the first few days. After that, the rate of loss tapers off.

The “Forgetting Curve” graphically shows that 90% of what most learn is lost within the first month. Whether you’re training salespeople to close more deals faster or contact center service agents to reduce average handle times (AHTs) on calls with customers, the importance, if not the imperative, of building retention activities into any learning program cannot be understated.

We can thank Ebbinghaus for showing us how to do that too. He found each time a training is reinforced the rate of decline, the amount forgotten, reduces. That means if you test someone’s memory, it becomes stronger. Doing that in a programmatic manner helps people retain information.

Not only should this be done with frequency but employing different learning vehicles, like an article, a diagram or infographic, even a video. If that’s needed to make clear what needs to be learned and maintained in the mind, do it.

If you accept the notion that each employee is different, then you’ll accept my view that each learns differently. And that makes the case for personalized learning, ideally personalized microlearning. I’ve seen many instances where an individualized approach yields better results for an organization as a whole. Along with personalized learning, the approach has to be relevant to employees and what their jobs entail, what skills need to be honed, and what behaviors need to be changed or reinforced.

So what about the notion that some people simply have bad memories and this approach won’t work with them. It’s literally an urban legend. Supposedly true but far from it. A memory, more accurately our memory network consists of those portions of the brain that help us to remember, to build our memory.

The first step in the process is to register a memory, also called encoding. For example, you meet someone and forget his name right away. That’s not a sign of a memory problem. The name hasn’t been encoded yet, likely because you weren’t paying attention to the person when he said his name. The next step is consolidation. Here a memory only becomes a memory if it’s registered. Then the final and, in some ways, the key step. It’s called retrieval and relates to Ebbinghaus’ concept of retraining to retain. Each time a memory is retrieved its gets stronger.

In a microlearning construct, especially one highly personalized, repeated exposure to a learning exercise builds the memory — even if the person answers quizzes incorrectly. It’s a learning experience that serves to strengthen the pathway to information in the memory network. If that person speaks with a customer, getting to the information relevant to that conversation becomes easier. The information that gets retrieved gets to be more accurate, more complete, with retraining, and the ability for it to be easily accessed in the memory network gets better. With short learning interactions, as little as a minute a day, performance will improve.

Evaluating whether employees are truly benefitting from this retrieval-retrain-store process it is not enough to see if they are answering the questions posed in the microlearning correctly. That only measures proficiency. It doesn’t indicate what they’ve been able to sell or satisfy a customer, and more. You need to be able to look at both knowledge gaps and performance gaps in tandem. And to do so not retroactively but in real-time to take action on those insights when it matters most — immediately.

This can happen best when the key elements of advanced gamification, personalized microlearning and real-time performance management are used holistically and with the aid of an automated platform to present, capture and analyze the learning and, in a nod to Ebbinghaus, retain.

Engage and motivate your frontline teams

Improve performance with an AI-powered digital coach

Deliver world class CX with dynamic, actionable quality evaluations

Boost performance with personalized, actionable goals

Nurture employee success with the power of AI

Listen and respond to your frontline, continuously

Drive productivity with performance-driven learning that sticks

Drive agent efficiency, deliver client results

Keep tech teams motivated and proficient on products and services while exceeding targets

Maintain compliance while building customer happiness and loyalty

Enlighten energy teams to boost engagement

Engage, develop, and retain your agents while driving better CX

Improve the employee experience for your reservations and service desk agents

Madeleine Freind

Madeleine Freind

Natalie Roth

Natalie Roth Linat Mart

Linat Mart

Doron Neumann

Doron Neumann Gal Rimon

Gal Rimon Daphne Saragosti

Daphne Saragosti Ella Davidson

Ella Davidson Ariel Herman

Ariel Herman Ronen Botzer

Ronen Botzer