When you think about motivation without giving it too much thought, you can end up arguing that people are only driven by money. This line of thinking implies that the more money you give, the better the work. This assumption then ties into bonuses and other forms of financial rewards. But, if you’re out to learn what Dan Ariely, the James B. Duke Professor of Psychology and Behavioural Economics at Duke University, you’ll discover that that is a shallow and misleading understanding of the nature of work and motivation.

Ariely says that this isn’t the only misleading understanding. For instance, if hobbies are supposed to be fun – why don’t mountaineers say it was fun to climb a mountain? Ariely says that if you read a mountaineering book, all you’d read is how miserable the experience was. Even when mountaineers say they’ll never go through the entire ordeal again, they do it again, and again and again. This means motivation isn’t all it seems to be.

What this all means is that human motivation isn’t just about rewards or fun. It is about the challenge, about the ways you achieve it and about a host of intricate motivators that can drive us to do our best, even at work.

Here are some key learnings from Ariely:

Would you like to be Sisyphus? Your employees wouldn’t want that either

Let’s say your boss asked you to prepare this huge presentation for the management team – and you did – working on it for days and nights. Let’s say that you are also told by your boss, after you finished the presentation, that there is no need for it, since the company chose a different strategy. That’s upsetting, of course. The question is how does that impact motivation. Ariely decided to conduct an experiment to check that.

In the first experiment participants were given a Lego Bionicle. They were offered $ 3 to assemble it. After they were done, the conductor of the experiment took the assembled Bionicle and put it under the table. He asked whether the participant wants to build another one, this time for $ 2.70. After that one was done, they were offered the same deal with the same 30 cent price cut, as so on, till they gave up.

The second version of the experiment worked the exact same way, only that assembled Bionicles were not stored under the table but dis-assembled right in front of the eyes of the participant. When the Bionicles stayed intact, participants built up to eleven of them. In the “Sisyphus condition” they only built seven. Destroying the Bionicles destroyed participants’ motivation.

Hard Work – people care about it

Another experiment tried to measure people’s attachment to their hard work. Participants were given origami paper and instructions on folding it to make origami. After finishing the origami, often with poor results, the experimenter mentions that the origami belongs to him, and asks how much people will be willing to pay to get it back. The same offer to buy the origami was also given to people that didn’t build the origami. The people building the origami bid five times higher than the offers made by the group of the people who didn’t build the origami. In fact, those who built the origami didn’t only think that their origami is beautiful, but they were certain that everyone else will love it as much as they do. This tells us that people value their hard work, not according to the actual result, but according to the effort they have put into it.

Cash Doesn’t matter that much

What if we were to question the conservative way of thinking about motivating people to work? Dan Ariely had done just that in an experiment he had conducted in India a few years ago. The participants of the experiment were given reward according to a certain level they have reached in the game. Small, medium or large cash reward. The small reward was a working day wage, the medium was 2 weeks’ pay and the Large reward was a 5 months’ pay. And what were the result, you ask? The small and medium reward groups were performing more or less in the same level, as the large reward group had performed quite poorly. The conclusion that was made from this experiment was, according to Ariely, that “one cannot assume that introducing or raising incentives always improve performance”. And in other words, Better pay doesn’t always mean better performance.

Taking it to the workplace

Taking these conclusions to the workplace can be tricky as we are adding more “noise” to the system. However, Ariely’s conclusions can be extremely valuable when trying to understand the current way to motivate your employees. Understanding and changing their behavior to improve results. Read more about gamification in the workplace here.

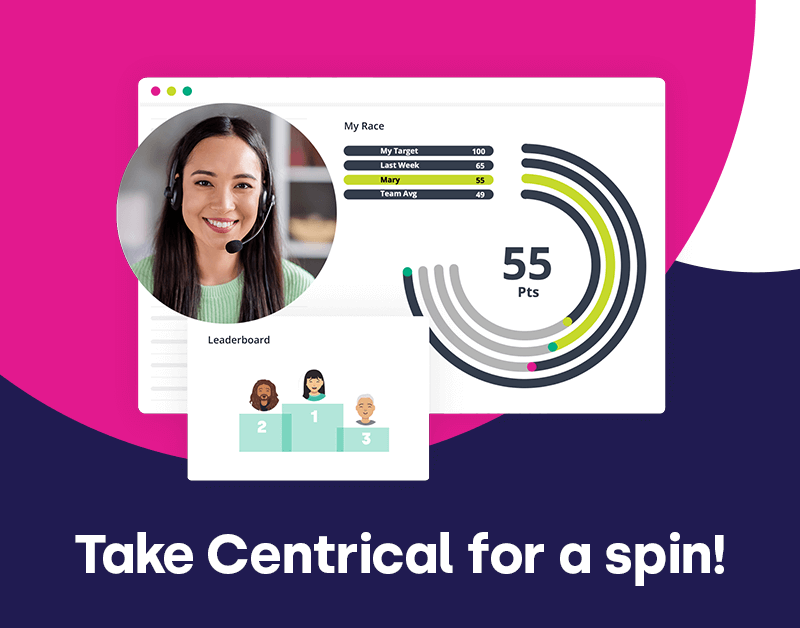

Engage and motivate your frontline teams

Improve performance with an AI-powered digital coach

Deliver world class CX with dynamic, actionable quality evaluations

Boost performance with personalized, actionable goals

Nurture employee success with the power of AI

Listen and respond to your frontline, continuously

Drive productivity with performance-driven learning that sticks

Drive agent efficiency, deliver client results

Keep tech teams motivated and proficient on products and services while exceeding targets

Maintain compliance while building customer happiness and loyalty

Enlighten energy teams to boost engagement

Engage, develop, and retain your agents while driving better CX

Improve the employee experience for your reservations and service desk agents

Madeleine Freind

Madeleine Freind

Natalie Roth

Natalie Roth Linat Mart

Linat Mart

Doron Neumann

Doron Neumann Gal Rimon

Gal Rimon Daphne Saragosti

Daphne Saragosti Ella Davidson

Ella Davidson Ariel Herman

Ariel Herman Ronen Botzer

Ronen Botzer