“Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business”

is a New York Times Bestseller by Charles Duhigg. It shows us recent scientific discoveries that explain why habits exist and how they can be transformed. It follows corporations and individuals that achieved success by focusing on the patterns that shape every aspect of our lives – transforming habits.

Most of the choices we make each and every day are not the products of well-considered choices. They are the products of habit;

we are creatures of habit. Habits range from small gestures: like what how we say goodbye to our kids in the morning to complex habits, such as backing a car from a driveway. According to the book, a Duke University researcher found that more than 40 percent of the actions people performed each day weren’t actual decisions but rather habits.

The book examines recent research and insights on the power of habit: how habits emerge in our life, what it takes to build new habits and change old ones. It also examines the habits that makes companies and organizations successful, from Starbucks to Alcoa.

Habits – acquired behavior patterns that are regularly followed until they become, in a sense, involuntary – have an enormous impact on our lives. Bad habits can turn someone’s life upside down and earn them social disdain. Good habits – from interpersonal exchanges to willpower and perseverance – are the cornerstone of success.

“Habits, scientists say, emerge because the brain is constantly looking for ways to save effort. Left to its own devices, the brain will try to make almost any routine into a habit, because habits allow our minds to ramp down more often. This effort-saving instinct is a huge advantage… An efficient brain also allows us to stop thinking constantly about basic behaviors, such as walking and choosing what to eat, so we can devote mental energy to inventing spears, irrigation systems, and, eventually, airplanes and video games.”

Dhuigg then goes on to explain how habits work, taking an example of a rat that hears a click, goes down the same route in a maze and then discovers chocolate at the same corner. At first the rat is startled by the click and is unsure what to do in the maze. After a while, a habit forms.

- A cue(the click) tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use.

- The routine tells you what to do (wait for the door into the maze to open and hang right)

- The reward (chocolate, a sense of satisfaction) helps your brain remember the habit and reinforce it.

In the same way when a ping alerts you that you’ve got email, the routine is to check it immediately, and the reward is distraction. Over time the habit forms a craving – in this case for distraction – which is enabled anytime there is a cue (phone pings), and satisfied only after the routine (checking the email) is followed. That’s why emails and instant messages sometimes become distractions that cannot be ignored.

Over time the cue, routine and reward loop become more and more automatic. The cue and reward are so interlinked in the brain that once the cue is given the reward is expected and going through the routine is automatic.

Duhigg then describes habit changes: since the cue, craving and the reward are difficult to change, some people focus on changing the routine that follows the cue. The classic example is eating a carrot when a craving for a cigarette is cued by an external factor (sitting with friends in a bar, for instance).

Enterprise Gamification, the practice of using game mechanics to promote behavioral change, is also about habit formation and changing habits. And changing organizational habits, by focus on a keystone habit, as Duhigg explains, can bring on tremendous organizational change.

Let’s say your sales people have one great habit: when a customer sounds doubtful, they immediately flood him with sales materials such as brochures and white papers. But their sales managers are not happy: they would also like the sales person to properly update the CRM about the customer’s doubts- that information is needed so that they can make meaningful forecasts. However, no requests, demands or threats make salespeople update the forecast regularly.

Perhaps driving sales people to update the CRM requires formation of a new habit – and also requires managers to think about the reward: will a sense of completion emerge or will salespeople will actually be rewarded? Or, perhaps the habit is reverse: when a customer expresses doubt, maybe sales people disengage. In this case the cue is there (fear of customer loss) but the routine and reward need to change.

One more thing about habits is that they take time to form and require repetition to be acquired and mastered. Desired behaviors need to morph into the automatic activity that requires little or no thought to perform. Gamification can be the tool that drives repetition and makes desired behaviors into habits, effectively removing the need for gamification since the activity has become intrinsically motivated.

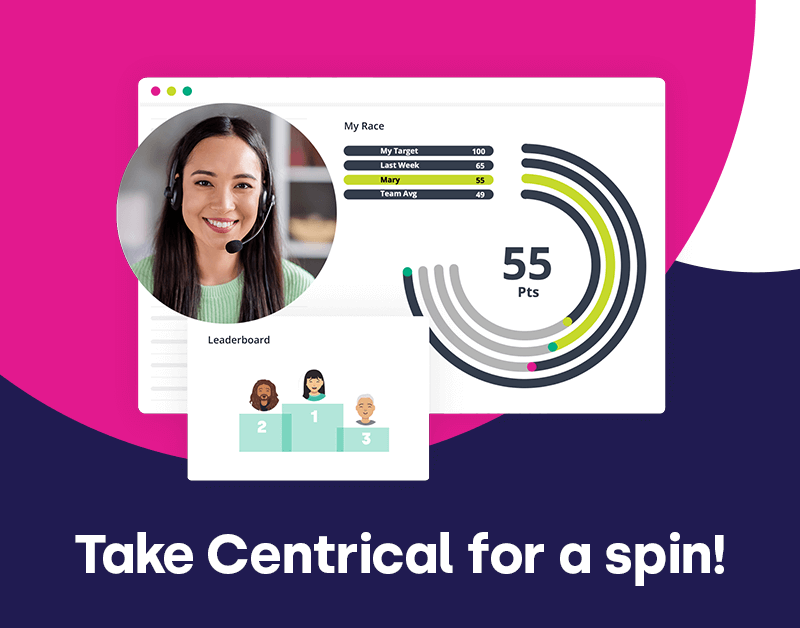

Engage and motivate your frontline teams

Improve performance with an AI-powered digital coach

Deliver world class CX with dynamic, actionable quality evaluations

Boost performance with personalized, actionable goals

Nurture employee success with the power of AI

Listen and respond to your frontline, continuously

Drive productivity with performance-driven learning that sticks

Drive agent efficiency, deliver client results

Keep tech teams motivated and proficient on products and services while exceeding targets

Maintain compliance while building customer happiness and loyalty

Enlighten energy teams to boost engagement

Engage, develop, and retain your agents while driving better CX

Improve the employee experience for your reservations and service desk agents

Madeleine Freind

Madeleine Freind

Natalie Roth

Natalie Roth Linat Mart

Linat Mart

Doron Neumann

Doron Neumann Gal Rimon

Gal Rimon Daphne Saragosti

Daphne Saragosti Ella Davidson

Ella Davidson Ariel Herman

Ariel Herman Ronen Botzer

Ronen Botzer