Foursquare’s recent changes can give us excellent hints about what works and what doesn’t in enterprise gamification design.

Remember Foursquare?

In 2009, Foursquare launched a location based social network that allowed you to “check-in” at various venues, turning “life into a game”. The service was initially limited to certain metro areas, but after it opened, it reached 10 million users, which enabled the company to raise $ 50 M in 2011 at a valuation of $ 600 M. Foursquare was a hit.

One of the core drivers behind the craze to check-in using Foursquare and not competing services was Foursquare’s use of gamification. Gamification is the practice of using game design elements to reward behavior in a non-game setting. It can be used to reward interaction with a service, such as Foursquare, or to reward a desired enterprise-related behavior as in Enterprise Gamification for employees. Foursquare gamified check-ins, letting users get points for certain activities (such as checking into a new place), get badges for checking in and even get mayor status, if a user checked into a certain venue on more days than anyone else in the past 60 days. However, social networks caught up with location based check-ins and Foursquare’s status eroded. Its enormous popularity tapered off.

Recently Foursquare separated its check-in service into an app called swarm and the new Foursquare, which “learns what you like and leads you to the places you’ll love”. Earlier Foursquare even ceased its famous points and badges system, the drivers of its immense popularity in the first place. This is what Foursquare says about its realization that its game mechanics were breaking down:

“…When we built Foursquare, the game mechanics were meant to do two things: help you learn how to use Foursquare, and help make your real-world experiences more fun. We never set out to make a ‘game’… Points gave you a way to measure how exciting your outings were; badges were to give you a sense of accomplishment; and mayorships allowed you to compete with your friends… even we were surprised by how much people loved them.

Back in 2009 when we had 50,000 people using Foursquare, they were awesome. But as our community grew from 50,000 people to over 50,000,000 today, our game mechanics started to break down.”

Now Foursquare wants to move into the local search space, targeting yelp and google reviews for places such as restaurants. And to do that it needs users to create a lot of reviews, so it can offer meaningful reviews and compete in the restaurant search space. As a result, the company is introducing a new kind of status – expert. Expertise is a function of the user’s performance within foursquare and not outside of it (the opposite of the Linkedin influencer, whose expertise is external to the Linkedin service). This should encourage users to review more places and submit more tips, making the Foursquare service valuable.

The story of Foursquare holds a valuable truth: Gamification mechanics are powerful and can drive user behavior; but the behavior has to contain an intrinsic value without the game mechanics. Gamification is not an end in itself; it is a design choice intended to drive real value. Foursquare is a prime example of gamification of a consumer service. What can enterprise gamification practitioners learn from it? Here are some that come to mind:

1. Gamification cannot drive long-term behavioral change.

Well, let’s take it back. As the CEO of an enterprise gamification company, Centrical, I deeply believe that gamification can drive change. I’ve seen it happen with my own eyes. But the trick is that rewards aren’t enough; the activity or behavior promoted needs to have an intrinsic value. At first, people were going out of their way to earn foursquare badges and mayorships. But these rewards didn’t suffice in the longer term because once novelty wears off and the fun becomes yesterday’s news, users need additional value. In the enterprise space this means that employees can’t just be rewarded for anything – rewards should be for behaviors that have real value to the organization and the employee, not just for their own sake. This will create a virtuous cycle that will drive employees to continue with the behavioral change even when the gamification novelty has worn off. This also means that gamification should reward behavior that has a real value for the company: if you reward contributions to a knowledge management system that no one uses, or reward employees for unnecessary customer visits, the results can be dire. Choose the desired behaviors you want to drive carefully; make sure they have a real meaning within your organization and that they reflect corporate goals.

2. Gamification works in content generation settings – but only to a certain degree.

Content gamification works in scenarios such as restaurant reviews and knowledge collaboration systems – but it should contain an element of recognition. Rewards without recognition of someone as an expert won’t work in the long run.

3. Badges and points still matter – but to a lesser degree.

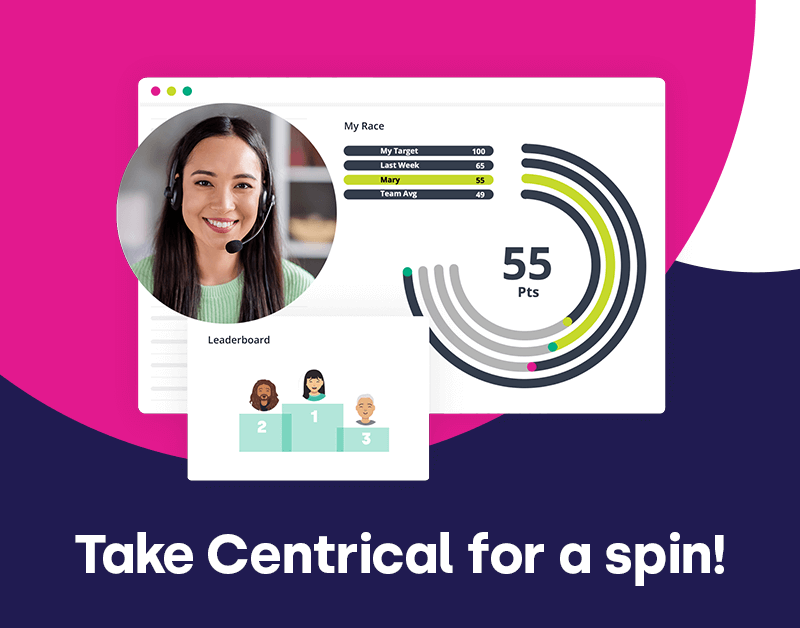

Badges are still part of the game mechanics arsenal any gamification solution should include. But they should be used judiciously, when they fit and not as an all-around solution. Sometimes giving employees a sense of completion matters too, as I wrote here – badges are more competitive in nature, but can also be adjusted to reward completion. Foursquare is also doing that in its new Swarm application by notifying users when they’ve taken many runs or hooked up often with a friend. The balance between completion and competition requires thought during the game design phase. The use of narratives in game design are also a new game mechanic some vendors (such as Centrical) are adopting, since they promote teamwork and the ability to balance several competing goals (such as good service vs quick service).

4. Not everyone can be a mayor; good game design gives them a good reason to try.

Leaderboards and competitive game mechanics can work, but you never want to alienate the non-mayors of the world. Enterprise gamification leaderboards should be designed so that they reward people in context and give people a sense of achievement. To resolve issues with Mayorships, in which too many people were competing for mayorship, Foursqaure revised its system to “Mayorship 2.0”. This is how Foursquare’s bog describes this. “We wanted to get back to a fun way to compete with your friends instead of all 50,000,000 people who are on Foursquare. With these new mayorships, if you and a couple friends have been checking in to a place, the person who has been there the most lately gets a crown sticker. So you and your friends can compete for the mayorship of your favorite bar, without having to worry about the guy who is there every. single. day.”

Engage and motivate your frontline teams

Improve performance with an AI-powered digital coach

Deliver world class CX with dynamic, actionable quality evaluations

Boost performance with personalized, actionable goals

Nurture employee success with the power of AI

Listen and respond to your frontline, continuously

Drive productivity with performance-driven learning that sticks

Drive agent efficiency, deliver client results

Keep tech teams motivated and proficient on products and services while exceeding targets

Maintain compliance while building customer happiness and loyalty

Enlighten energy teams to boost engagement

Engage, develop, and retain your agents while driving better CX

Improve the employee experience for your reservations and service desk agents

Dalit Sadeh

Dalit Sadeh April Crichlow

April Crichlow Ella Davidson

Ella Davidson Linat Mart

Linat Mart Gal Rimon

Gal Rimon Jayme Smithers

Jayme Smithers Doron Neumann

Doron Neumann Daphne Saragosti

Daphne Saragosti Ronen Botzer

Ronen Botzer Ariel Herman

Ariel Herman